I’ve been baking a lot of cookies. Every morning I wake up with a thousand things to do, and all I actually want to do is pull out the butter and the sugar and the eggs and the chocolate chips and make something with my hands. In the olden days, I’d put on The Daily or NPR, but no thanks, not today. I’ve been listening to Gracie Abrams on repeat, thanks to the tween, and sing along (very poorly, I really don’t understand half the lyrics) and try to feel a single thing.

The cookies have nowhere to go, really. There are only three of us, one is a vegan, and the tween is so discerning about sweets that she will often take one bite, shrug and move onto something else (this is what happens when your mother bakes all the time). I tend to pawn them off on neighbors, and lately, my students, who are the most appreciative bunch. I store them in my freezer for when guests come over. These are the times I wish I had four teenagers, or worked in an office or a school. Here’s more! There’s always more! Please, take — take!

Everyone I know has said they are turning inward — to their own kitchens, their own homes, their families, their communities. My sudden revelation on November 7th was that this time around I was not going to give him my mind, I was not going to be drawn into every headline, I was not going to fall for the shock and awe of it all, I was not going to sign every petition and call every senator and drop my whole life so I could run off to the airport for yet another protest. Last time, I had allowed my life to overlap almost entirely with the drama of it all, and I could not live this way again. I passed out this brilliant essay by Lan Samantha Chang to my grad students and said, please, find a way to do this, protect your inner lives. Do it at all cost.

The result, of course, is that I feel almost entirely numb. I hear about the nominations, and where outrage once was, now I feel a dull tug. In the days before the election, the thought of RFK Jr. being in charge of our health made me feel — ironically! — physically ill. And now I’ve somehow moved it to the periphery, the reality that a vaccine-denier will somehow tell me how and when to vaccinate my child (according to him, never).

Some would say this glazing over is sane and smart and protective; others would say it’s a privilege; others still: an outrage. Like most people, I am simply trying to find a way to move forward with my everyday life: travel from bed to coffee to school drop-off to work and back again while getting in some exercise and protein and sleep. Now — for now, it will be brief, I know — I am one of those people who is paying little attention and then just goes into the voting booth and says, I guess, who knows, that guy? (My hatred for those people is still flaming hot.)

I know I will not be able to live this way for long. Over grim drinks on the Friday after the election, my friend Ali and I were joking that we were taking a news break but I did read this one thing, and I listened to this other thing, and I watched Jon Stewart, and also did you see —? The pull, for many of us, to know, to do something, is stronger than our own resolve to get a break.

But this is, perhaps, the lesson of 2016: the limits of what we can do. I picture young(ish) me, walking to the coffee shop where I wrote every morning after I dropped my then three-year-old at preschool, calling every senator’s office to get them to reject every single nomination — those 15 minutes on the phone meant something to me, I thought they meant something, period, but they were useless, really. Did John McCain’s office care about someone in California calling to tell him to vote No on the repeal of Obamacare? Ditto for all the other “good” Republicans, you know who they are. They didn’t want to hear from us. They weren’t working for us. This has become all too clear.

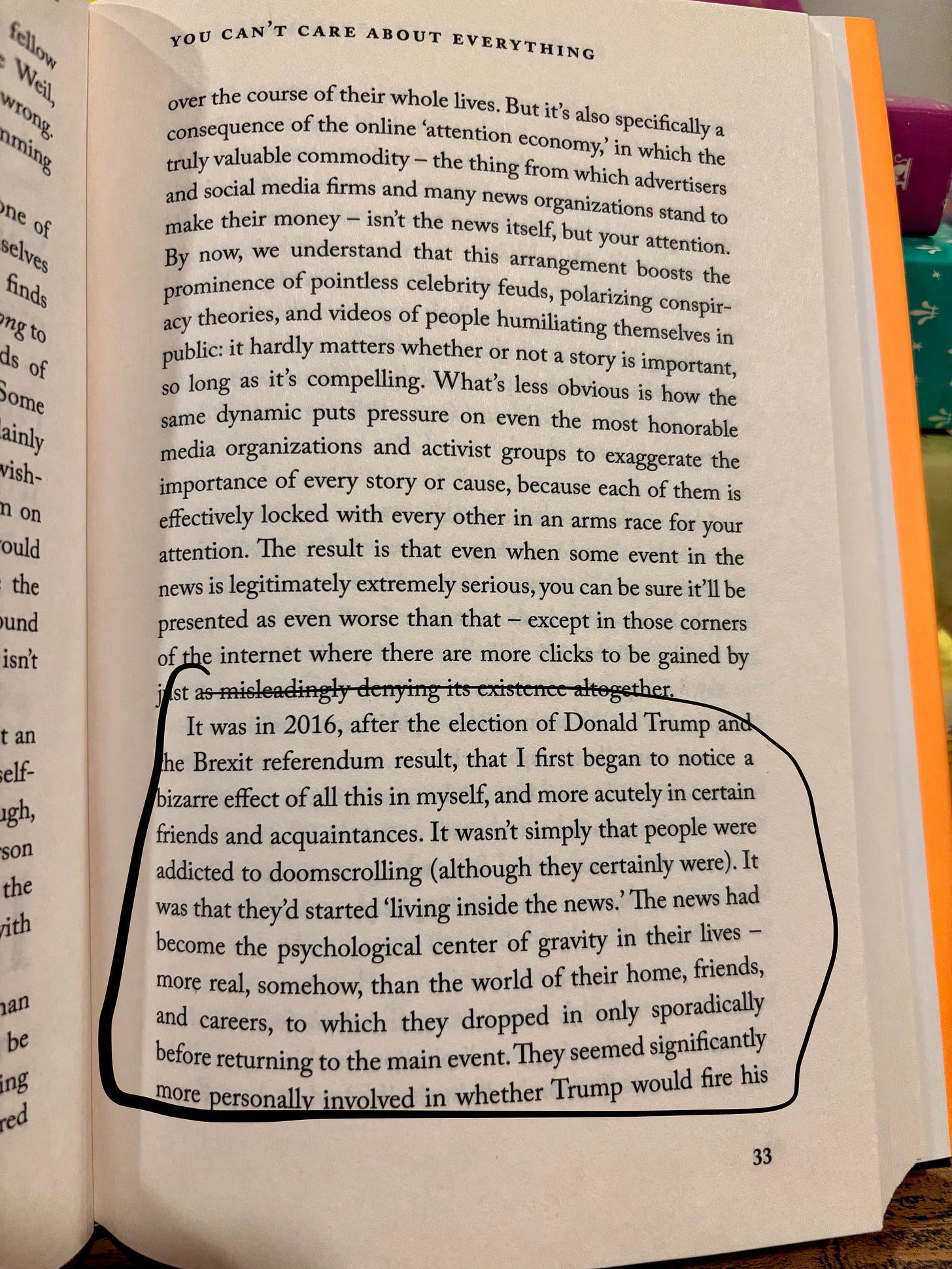

The most stunning thing I’ve read in the last few weeks is from Oliver Burkeman’s new book, Meditations for Mortals. I was so alarmed by the veracity of this one chapter that I took a photos of the entire thing and sent them along to many friends. The chapter is aptly titled, “You Can’t Care About Everything.” He warns about the dangers of letting your psychological well-being be to intrinsically tied to all the events of the world — of taking the news as seriously (or more) than our own lives. He cautions that, as humans, we can only care so deeply — and do so much — about so many things. Not that many, it turns out! And we are better off devoting ourselves entirely to those things and not expending all of our outrage on things we have no control over.

Living inside the news! Was there ever a more apt way of putting it? None of this is to suggest any of us should check out entirely, or that many of us even can. Many things that are about to unfold will impact us directly: mass deportations, the repeal of Roe and all sorts of other horrifying restrictions of women’s reproductive care, a lunatic in charge of HHS. But what Burkeman writes rings frighteningly true. What did I miss right in front of my face when I was too busy making sure I’d reached Susan Collins? How much time did I spend letting my mind get sucked into one endless political drama after another instead of focusing on writing my book?

This is not a simple time, and I can’t pretend to know a single thing. Right now — November 2024 — we are in a kind of bardo, we are drifting off from what we’ve known but have not yet arrived anywhere new. It’s like Jo Ann Beard writes in “The Fourth State of Matter”:

“In a few hours the world will resume itself, but for now we’re in a pocket of silence. We’re in the plasmapause, a place of equilibrium, where the forces of the Earth meet the forces of the sun. I imagine it as a place of silence, where the particles of dust stop spinning and hang motionless in deep space.”

In this place, I am turning to what I can touch: the people and things that surround me, that keep me tethered to my actual life: the butter that goes bad, the eggs that need to be restocked, the cookies that need to be wrapped up and given away. It is not a giving up, it is not a ceding. It is a drilling down, it is an awakening to what is right before my eyes.

I am not, of course, suggesting cookies are the answer. But right now, they are serving their purpose: to remind me of where I actually live, small “l.” Not only in the United States of America — which feels as foreign to me as ever — but in my city, on my block, in this apartment building, in this kitchen, with this family.

I do think we will all, eventually, learn that we can do many things at once, like we did during that long last round: Take care of ourselves and tend to those who need us most. Protest when we need to, and also relish cuddles on the couch without simultaneously reaching for the latest headline, knowing the most immediate, pressing headline is just beside us, body curled into ours.

Sending love,

Abs xox

Thank you for this. Some sources I've read have suggested that getting us to "live in the news" through the sheer VOLUME of the nonsense (I mean noise and excess) is a strategy to keep us mired in overwhelm and outrage instead of concerted, careful action. I've been thinking about that: how maintaining my capacity to think a whole thought all the way to its end, to pay attention to what matters, including the physical world around me (butter, sugar, eggs, neighbours, students, children, partner, friends, beauty) is essential in the long game.

the bardo, yes. and that passage made me want to read that whole book. I don't want to live in the news!